Obstructive sleep apnoea, atrial fibrillation and erectile dysfunction (OSAFED) syndrome was initially introduced into the literature several years ago by Szymanski et al.1 The OSAFED acronym consists of the first letters of the three clinical entities that are included into the disease, namely obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), atrial fibrillation (AF) and erectile dysfunction (ED). The requirement for its first description arose from the fact that the three above-mentioned diseases are not only extremely common in the general population, but have common risk factors, aetiology and consequences. As with many other clinical syndromes, the OSAFED syndrome groups several clinical entities, which seemingly concern different organs and have different symptoms, but are closely associated by sharing risk factors and phenotype and effecting cardiovascular risk in the same manner. As it will be explained below OSAFED syndrome is one of the pathologies associated with a rather common clinical phenotype, which is often observed in cardiology clinic patients. Of course, in modern medicine we rarely can make a diagnosis simply by looking at the patient, but several phenotypes allow physicians to perform further tests or look for other diseases. This is the case in OSAFED syndrome. Its main and sole purpose was to raise awareness of the co-prevalence of those three conditions in general practice and the necessity for physicians to screen and evaluate patients with one of the diseases for the remaining two. For example, we postulate the necessity of initial screening, for example, in all AF patients (using easy to apply, standardised questionnaires) for OSA and ED. Early detection on all diseases included in the OSAFED syndrome may not only facilitate early diagnosis of patients at risk, but also may improve their prognosis by the introduction of proper treatment and reduction of the total cardiovascular risk.

This review summarises the evidence linking three apparently unrelated cardiovascular conditions, which not only frequently coexist as they result from clustering of common risk factors, but also negatively potentiated their individual impact on psychosomatic health and cardiovascular risk of affected patients. In this article, we will focus on some of the proposed mechanisms that may account for occurrence of OSAFED in the general population patients.

Epidemiology of the Components of the OSAFED Syndrome

OSA – the first of the diseases mentioned in the acronym – is one of the types of sleep-disordered breathing most prevalent in the general population. The data on the prevalence of OSA varies greatly in the literature. Most of all this is due to the differences in the methods and definitions used. The most widely cited paper concerning the prevalence of OSA estimates that approximately 24 % of men and 9 % of women have the disease. And the definition used in the paper was apnoea–hypopnoea index (>5/hour).2 Nevertheless, recently we observed that several sleep scoring manuals have been published, each one containing different threshold values for the diagnosis of individual sleep episodes.3–5 Scoring according to the different manuals generates a large bias, which make the epidemiological studies hard to interpret.6 Moreover, many of the studies describing the prevalence of OSA in the population tend to incorporate

only patients with daytime symptoms of the disease. Therefore, the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in the general population is either not properly reported or is underestimated. Moreover, in the last few decades we witness not only prolongation of life expectancy, but also a global epidemic of obesity, which accounts for the changes in the prevalence of OSA. Newer data showing the prevalence of the disease to be between 14–55 % seem more reasonable nowadays, along with other studies showing the prevalence of OSA to be as high as 62 % in patients aged >65 years.7,8 As for the prevalence of OSA in patients with AF or ED, the data show a correlation between the diseases. In patients with OSA (and coronary artery disease), the likelihood of being diagnosed with ED is over 50 times higher than in those without sleep-disordered breathing.9,10 Also, OSA has been described a number of times to be associated with AF development promotion and negative outcomes in patients in whom the rhythm control strategy is undertaken.11,12 In the young AF patient population, OSA was present in 45.5 % of patients, which is more than in the general population.13

Out of the three above-mentioned diseases, the prevalence of AF is best described. Most of the sources state that in the general population, arrhythmia is present in 2 to 4 % of patients, but those data also concern an epidemic situation from a few decades ago. Today, due to the prolonged monitoring and registration from implanted cardiac devices, in fact we know that AF afflicts many more patients. Also, due to prolonged life expectancy, that total number of AF patients is estimated to triple by the end of year 2060.14 By this time there will be about 18 million AF patients in the EU alone. Of course, as in the case of OSA, in AF patients several risk factors also contribute negatively to the development of the disease. It is well-known, that body mass correlates with AF. It is estimated that about one-quarter of AF patients are obese, and the mean body mass index of this population is 27.5 kg/m2, which meets the criteria for overweight diagnosis.1

Perhaps the least data are available on the prevalence of ED in the general population. In men, ED usually is an effect of mutual exacerbation of several conditions concerning vascular, hormonal, neurological and psychiatric functions. Physicians of many specialties rarely ask patients about their sexual health and therefore an objective scale of the problem is difficult to diagnose. Even the epidemiological studies in most cases are based on questionnaires rather than objective measures of erection hardness and the ability to maintain it. Nevertheless, the literature shows that it occurs in 18 % to 40 % of men older than 20 years.15,16 As in the previous cases, the ED prevalence also rises significantly with age, being almost four times more prevalent by the 50–59 years of age than in 18–24 year olds.17

Clinical Presentation and Cardiovascular Risk Associated with the OSAFED Syndrome

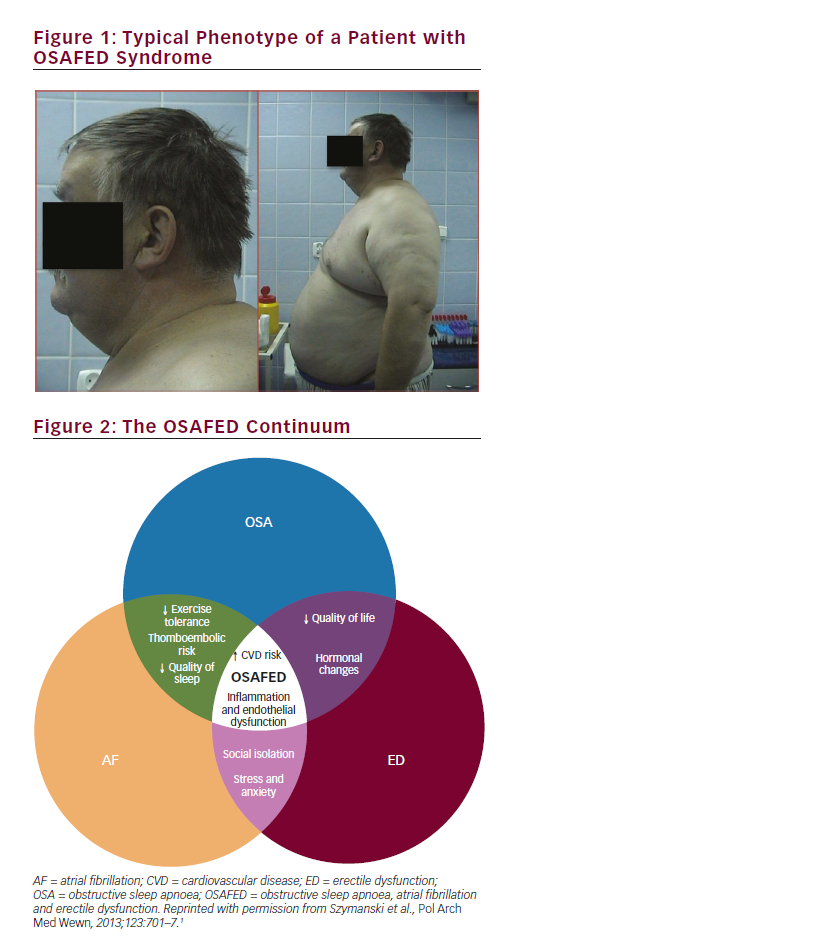

As shown in the previous paragraph, all three diseases are more often present in older, male patients with obesity (in the case of ED – abdominal obesity, while in OSA, especially when a large amount of fat is present around the neck area). In Figure 1, a typical OSAFED patient is depicted – this individual was initially referred to the hospital due to AF. In this case along with severe obesity, older age, a short, fatty neck draws attention. Medical examination revealed that, in fact, the patient suffered from irregular snoring and daytime sleepiness, he also complained of ED for several years, but never mentioned this to his doctor. We must ask ourselves how often we encounter patients like that in everyday practice?

But older age and obesity are not the only problems in OSAFED patients. As we showed in our initial paper,1 OSAFED is a combination of risk factors common for the disease that by coexistence in a single patient exacerbate the course of each other and end up making the disease more severe. Figure 2 shows how complex the OSAFED pathophysiology is and demonstrates the role of OSA, AF and ED in the development of the syndrome. In the centre of the figure we can see that the two main consequences of the OSAFED are inflammation with endothelial dysfunction and an increased cardiovascular risk.

The pathophysiology of the OSAFED syndrome starts from the cellular level, but is associated with alterations in tissues and organs. OSA, AF and ED are partially consequences of autonomic dysregulation, elevated sympathetic tone, oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction and abnormalities in blood vessels and heart chambers. An important link between the OSAFED components are oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction. Lower levels of nitric oxide, associated with hypoventilation in the course of OSA, are responsible for lack of vasodilatation, oxidative stress and impaired erection, also causing changes in atrial homeostasis.18–20 What is the practical meaning of these associations?

Up to now there have been no studies assessing the prevalence of OSA, AF and ED in a single cohort of patients, therefore we not only do not know the epidemiology of the OSAFED syndrome; however, what is more important, we also do not know what the impact of the OSAFED syndrome on the total cardiovascular risk profile is.

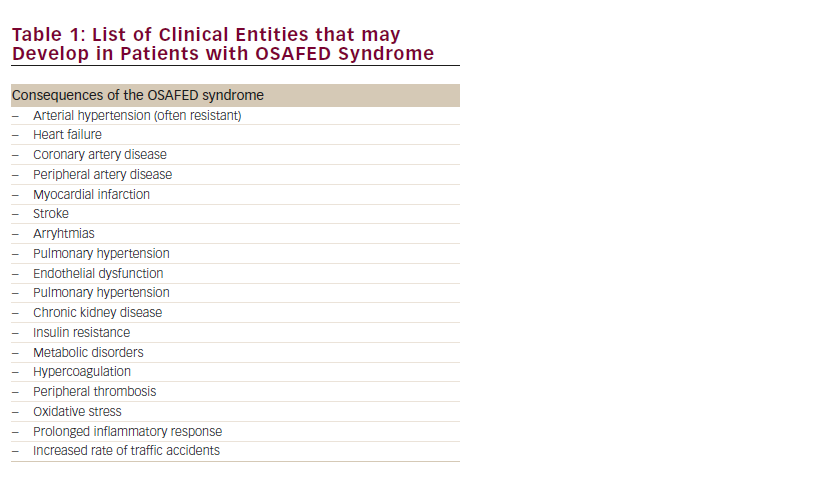

Each of the conditions included in the OSAFED syndrome is an independent risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease. On the one hand, it is associated with cardiovascular risk factors, on the other with cardiovascular disease itself. Table 1 summarises most of the diseases highly prevalent in OSAFED patients.

In OSA patients, the three perhaps most important, risk factors, i.e. hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes, are highly prevalent. Over one-half of OSA patients have hypertension and OSA is an event said to be one of the most important causes of the resistant hypertension.21 In fact, in normotensive patients, OSA increases the risk of hypertension development by three times;22 while type 2 diabetes is found in 15–30 % of patients.23 In this case the association may be mediated inflammation process and insulin resistance. Nevertheless, another metabolic component is found commonly in OSAFED patients. In OSA patients a significantly higher rate of hyperlipidaemia is noted, which perhaps might be mediated by intermittent hypoxia.24,25 All of this translates to an elevated risk of adverse events. Patients with OSA have an increased 10-year risk of fatal cardiovascular events by 2.87 times and risk of nonfatal events by 3.17 times.26 There are also many studies describing cardiovascular events related to OSA, including stroke and myocardial infarction. Therefore, it is necessary to identify and treat this disease early.

As for the AF, arrhythmia is one of the main causes of hospitalisation, disability and premature death in Europe. It is estimated that nearly one in every five of ischaemic strokes is directly caused by AF. One of the most important aspects of AF treatment is prevention of peripheral theromboembolism. Therefore, due to a strong recommendation that is included in the guidelines, the association must be kept in mind between AF and cardiovascular risk and cardiovascular events, mostly stroke.

Classic cardiovascular risk factors including older age, obesity, cigarette smoking, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and hypertension are associated with ED.27 However, there is another indicator: ED is one of the earliest and potentially treatable signs of any ongoing atherosclerotic process. The idea that we can diagnose or just suspect coronary artery disease simply by a patient telling us that he has an erectile problem is very promising, and may be useful in the future.

Thromboembolic Risk in the OSAFED Syndrome

In the context on the OSAFED syndrome, one more aspect should be mentioned and analysed. Thrombembolic risk is elevated and plays a prominent part in the development/consequences of all of them. When we are thinking of a cardiac disease we most often think about the AF, but the arrhythmia is not the only cause of the embolism. Also both other conditions – ED and OSA – may be associated with the risk of thromboembolism and when they coexist, they may produce an even greater risk.

The current guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology recommend the of use the CHA2DS2-VASc score, which on the basis of clinical risk factors, helps to estimate the stroke risk in AF patients.28 As has been described, the score does not incorporate all the parameters important in the risk stratification. In recent studies we showed that in AF patients with OSA the CHA2DS2-VASc and CHADS2 scores tend to be significantly higher than in patients without the sleep-disordered breathing, which translates into elevated stroke risk.29,30 Similarly, up to recently there have been no studies describing the association between AF, ED and thromboembolic risk. It turns out that like in patients with OSA, and the ED population, the thromboembolic risk assessed by the CHA2DS2-VASc and CHADS2 scores are significantly higher than in patients without ED.31

Microthrombi as well as normal-sized thrombi may develop during AF, OSA or in cases of ED. They are extremely dangerous for patients, potentially having the ability to close all the arteries, starting from the brain, through the heart and penile arteries.

In conclusion, all the examples mentioned above show that the OSAFED syndrome is a valid concept, which was introduced into the clinical practice quite recently and it warrants interest and has gained clinical importance. It is crucial for the clinician to improve the diagnosis and early treatment of all – OSA, AF and ED – and the incorporation of all these factors into one syndrome might help to facilitate this process.