Mitral valve (MV) disease includes either mitral regurgitation or mitral stenosis or both. The incidence and prevalence of valvular heart disease is increasing with the increasing population age. Degenerative MV disease poses a global burden with a prevalence of 18.1 million cases in 2017. Further, its global prevalence increased by 94% from 1990 to 2017.1 Surgery is the gold standard of treatment for significant MV disease; however, half of the symptomatic patients are unable to undergo surgery because of high procedural risk, significant comorbidities, or contraindications to surgery, which all pose a therapeutic challenge.2,3 This is particularly true in patients with mitral annular calcification (MAC). MAC is the fibrous and degenerative calcification of the MV, with significant MAC present in 8–15% of the population with MV disease.4,5 The prevalence of MAC increases with age, and its pathophysiology is similar to atherosclerotic calcification.6 MAC can lead to mitral stenosis, regurgitation or both.

Patients with MAC have an increased morbidity and mortality risk with MV surgery.7,8 Less invasive transcatheter repair procedures have been developed to overcome these challenges, leading to the introduction of the MitraClip™ system (Abbott Vascular-Structural Heart, Menlo Park, CA, USA).9 However, MitraClip is not feasable for several conditions with unfavourable MV anatomy, such as significant leaflet calcification, MAC with mitral stenosis, or regurgitation or short leaflets.10,11 Transcatheter MV replacement (TMVR) is emerging as a potential alternative treatment strategy in such patients when anatomy is suitable. First reports of TMVR in MAC with compassionate use of balloon-expandable transcatheter valves demonstrated success with surgical transapical or an open transatrial approach, followed by successful results via a percutaneous transfemoral approach.12–15

The current article reviews patient selection, preprocedural imaging clinical outcomes and the procedural complications of TMVR in patients with MAC.

The pathogenesis of mitral annular calcification

MAC is characterized by calcium accumulation along the mitral annulus, most commonly in the posterior aspect of the mitral annulus with posterior leaflet extension, although it can extend circumferentially. Originally thought to be a chronic age-related degenerative process with calcium deposition, MAC is now understood to be a molecularly active and monitored process of injury, lipid deposition, inflammation and bone formation.6 Sell et al. described a post-mortem study of the mitral annulus and histologically demonstrated lipid deposition among collagen that progressively became denser with age, followed by progressive calcification.16 Another autopsy report showed calcified and necrotic tissue in the collagen matrix along with inflammatory cell infiltration, angiogenesis, myofibroblastic differentiation of interstitial cells and lamellar bone formation.17 Imaging evidence by positron emission tomography has shown inflammatory activity in MAC by demonstrating 18F–fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.18 Risk factors associated with MAC include diabetes, hypertension, smoking, obesity, dyslipidemia, left ventricular hypertrophy, connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome or Hurler syndrome, chronic kidney disease, and importantly, female sex.19–21

Preprocedural Imaging

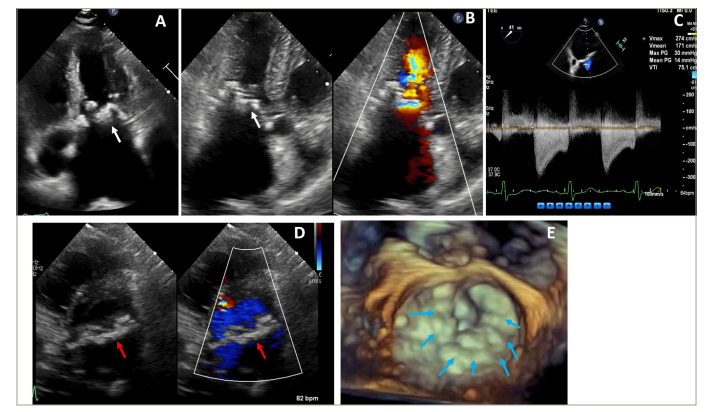

Imaging is crucial in assessing the anatomy and severity of the MV pathology. Transthoracic echocardiography and transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE) are standard imaging tools for assessing the MV and grade severity of valve dysfunction using standard American Society of Echocardiography guidelines.22 A detailed and comprehensive echocardiographic assessment in the context of transcatheter MV interventions is beyond the scope of this article and has already been well established in the literature.23–26 The echocardiographic assessment is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Echocardiographic assessment of a patient with severe calcific mitral stenosis

Figure 1A and 1B are long axis transthoracic echocardiography images demonstrating significant mitral annular calcification (white arrow) with severe left atrial enlargement. Figure 1C is a continuous wave Doppler showing severe mitral stenosis. Figure 1D is a short axis transthoracic echocardiography with and without colour demonstrating circumferential mitral annular calcification and mitral stenosis (red arrow). Figure 1E is a 3D transthoracic echocardiography showing circumferential mitral annular calcification (blue arrows).

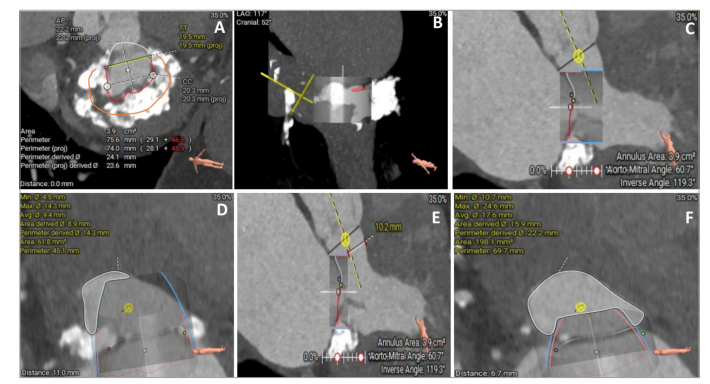

Figure 2: Multidetector computed tomography work–up for valve-in-mitral annular calcification transcatheter mitral valve replacement

Figure 2A is a multiplanar reconstruction showing circumferential mitral annular calcification (MAC) (orange contour showing 270 degrees circumferential MAC). Figures 2B–2D represent the prediction of neo-left ventricular outflow tract by the placement of virtual transcatheter mitral valve in MAC. Figures 2E and F are simulations of neo-left ventricular outflow tract with laceration of anterior mitral valve leaflet to prevent left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LAMPOON) technique assisted valve-in-MAC transcatheter mitral valve replacement.

Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) is an integral part of the assessment of MV anatomy, function and its relationship with adjacent structures before TMVR (Figure 2). Electrocardiographically gated MDCT allows us to retrospectively gather data throughout the cardiac cycle, which can be further reconstructed each 5% or 10% of the RR interval and in multiplanar reconstructions.27 Curved planar reformatted images permit the assessment of the entire course of the coronary artery (especially the circumflex artery which courses along the left atrioventricular groove, which is close to the mitral annulus), atherosclerotic lesions and vessel stenoses.28 A 3D and 4D volume rendering view can aid in the comprehensive assessment of the spatial distribution of MAC, MV and its adjacent structures.28 The MV short axis can be rebuilt using the double oblique transverse plane, and the orthogonal plane can be aligned across the lateral (A1 to P1), central (A2 to P2) and medial sections (A3 to P3) of the MV.29 By performing these reconstructive imaging methods in the end–systolic phase of the cardiac cycle, the underlying pathology of mitral stenosis or regurgitation can be recognized. The grade of mitral stenosis and regurgitation can also be delineated by calculating the anatomic MV and regurgitant orifice areas, respectively.29 MDCT also helps with accurately measuring the annulus and the burden of MV annular calcification; this is crucial for identifying TMVR feasibility. It can precisely measure the 3D size of the saddle-shaped, non-planar mitral annulus and localize the landing zone of the prosthesis. It also provides insight into leaflet anatomy, calcification and thickening; tenting height; papillary muscle anatomy; and tethering height compared with the annular plane.23 The information on the anatomical structures surrounding MV and its relationship to the MV is crucial for performing TMVR.

TMVR may lead to the obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) by the permanent displacement of the native anterior mitral leaflet towards the interventricular septum.30 This, in turn, creates a new compartment called neo-LVOT. It is important to note that the axis of the neo-LVOT is different from the axis of the native LVOT, so assessing the neo–LVOT area using MDCT helps predict LVOT obstruction (Figure 3).30 By placing a virtual valve in the mitral annulus, the neo–LVOT area can be predicted by MDCT in various systolic phases of the cardiac cycle.30 The MV plane, which is the lowest point of insertion of the mitral leaflets, is preferably measured at 40% of the cardiac cycle in the narrowest possible dimension of the neo-LVOT area.30 The assessment of neo-LVOT in TMVR is incompletely understood and is undergoing extensive evaluation in clinical trials. Yoon et al. showed that an estimated neo-LVOT area of ≤1.7 cm2 predicted LVOT obstruction with a sensitivity and specificity of 96.2% and 92.3%, respectively.31 Furthermore, post-TMVR LVOT obstruction was associated with higher procedural mortality. Wang et al. showed that a predicted neo-LVOT area of ≤1.894 cm2 predicted TMVR–induced LVOT obstruction with a sensitivity and specificity of 100.0% and 96.8%, respectively.32 Aortomitral angulation close to 90°, small left ventricular cavity and basal hypertrophy (<15 mm) were also found to be risk factors for post–TMVR LVOT obstruction.26 Septal hypertrophy is associated with high aortomitral angulation, which, in turn, also increases the risk of LVOT obstruction.26

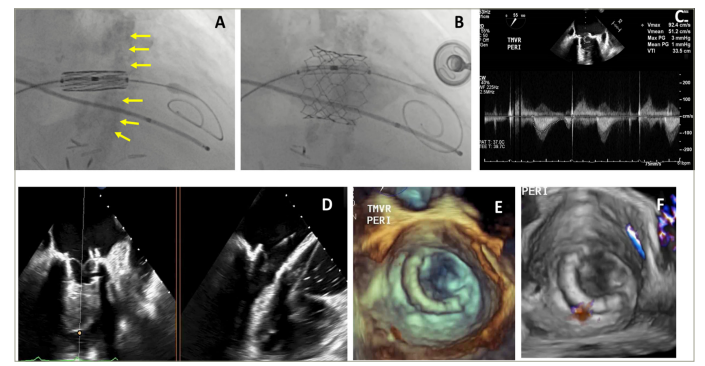

Figure 3: Valve-in-MAC transcatheter mitral valve replacement using the SAPIEN valve (Edwards Lifesciences LLC, Irvine, CA, USA)

Figures 3A and B are fluoroscopic images demonstrating the placement of a 26 mm SAPIEN 3 valve (Edwards Lifesciences LLC, Irvine, CA, USA) in mitral annular calcification during valve-in-mitral annular calcification (ViMAC) transcatheter mitral valve replacement and final position after balloon expansion. Figure 3C is a continuous wave Doppler demonstrating a mean gradient of 1 mmHg across the transcatheter mitral valve. Figure 3D is a biplane 2D (transoesophageal echocardiography) showing the leaflets of the transcatheter mitral valve after ViMAC transcatheter mitral valve replacement. Figures 3E and F represent a 3D a transoesophageal echocardiography with and without colour Doppler after ViMAC transcatheter mitral valve replacement.

Guerrero et al. proposed a computed tomography (CT)–based MAC scoring system for identifying MAC severity and predicting valve embolization when TMVR is conducted using balloon-expandable aortic transcatheter heart valves.33 This scoring system was devised using the average calcium thickness (mm), degree of the annulus circumference involved, calcification at one or both fibrous trigones, and calcification of one or both leaflets. The scores were categorized as mild (≤3 points), moderate (4–6 points) and severe (≥7 points). They also reported that mild–to–moderate MAC possesses a very high risk of valve embolization and that severe MAC carries a lower risk of valve embolization/migration.

Patient selection for transcatheter mitral valve replacement

Patient selection for TMVR in MAC patients depends on multiple factors: patient comorbidities, degree of symptoms and quality–of–life impairment despite the optimization of guideline–directed medical therapy, the anatomic risk of TMVR, the surgical risk for bailout, and local expertise in complex transcatheter and surgical interventions.32,33 Frailty has emerged as an important factor in predicting death or disability following structural interventions, including transcatheter aortic valve implantation and transcatheter mitral interventions.34,35 There are various tools to measure frailty. We use the Essential Frailty Toolset when evaluating patients for transcatheter valve interventions. A multidisciplinary heart team approach with close collaboration between interventional and imaging cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, heart failure specialists, and other relevant teams in a high-volume heart valve centre, is required for optimal patient selection and successful outcomes.

Procedural Technique for valve-in-mitral annular calcification transcatheter mitral valve replacement

Valve-in-MAC (ViMAC) TMVR using the SAPIEN valve (Edwards Lifesciences LLC, Irvine, CA, USA) can be performed via transapical, direct transatrial or, most commonly, transfemoral transseptal access. After the appropriate anatomical screening (as described above), for the transseptal approach, balloon atrial septostomy is performed with a 12 mm or 14 mm balloon over a pre-shaped stiff wire placed in the left ventricular apex. Alcohol septal ablation (ASA) or intentional laceration of the anterior MV leaflet (i.e. the Laceration of the Anterior Mitral leaflet to Prevent Outflow Obtruction [LAMPOON] procedure) may be performed depending on anatomic pre-screening and risk of LVOT obstruction. Using angles predicted by the preprocedure CT and live TEE and fluoroscopy guidance, the balloon–expandable SAPIEN valve is advanced across the septostomy into the mitral annulus, ensuring optimal coaxiality. The valve is then carefully deployed under rapid pacing to achieve an 80/20 (80% ventricular) position. Post–dilation may be necessary if paravalvular regurgitation is noted. LVOT and mitral haemodynamics are then assessed. This procedural technique is described in Figure 3. Its complications and their management are discussed below.

Clinical Outcomes of valve-in-mitral annular calcification transcatheter mitral valve replacement

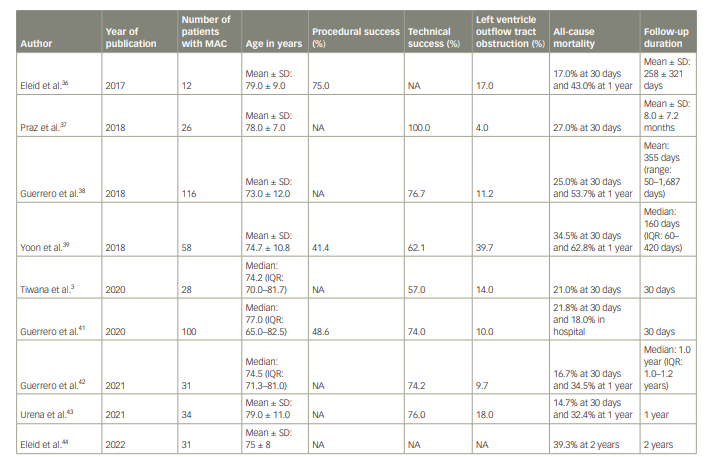

Eleid et al. performed percutaneous TMVR in 12 severe patients with MAC.36 At 30 days, 10 patients were alive, with 9 out of 10 showing clinical improvement of their symptoms. The 1-year survival rate was 57%, with four patients reaching the 1–year follow–up date. Of those four patients, three had New York Heart Association (NYHA) class I or II symptoms, and one had NYHA class II symptoms. In addition, two of these patients even had a 2–year follow–up with continued NYHA class II symptoms. Praz et al. studied transatrial TMVR in 26 patients with MAC and reported 100% technical success.37 Furthermore, there was considerable improvement in NYHA functional class. The 30-day mortality was 27%: five patients died during the hospital stay (19%), and two died between discharge and the 30–day follow–up. Two patients died after 30 days, and longer–term follow–up was seen in 15 patients. In the MAC Global Registry, Guerrero et al. reported 1–year outcomes of TMVR using balloon-expandable aortic valves in 116 patients with severe MAC.38 LVOT obstruction with haemodynamic compromise occurred in 13 patients (11.2%) and showed high in-hospital mortality. The 30–day and 1–year all-cause mortality were 25.0% and 53.7%, respectively. Most patients who survived 30 days were alive at 1 year (63.6%). The majority of patients (71.8%) improved to NYHA class I or II after undergoing TMVR. In this study, LVOT obstruction was the most important and independent predictor of 30–day and 1–year mortality. In the TMVR multicentre registry, Yoon et al. studied the outcomes of TMVR in 521 patients, 58 of whom underwent ViMAC TMVR.39 For these patients, technical success rate was 62.1%. LVOT obstruction occurred most often with ViMAC TMVR cases (39.7%), while second valve implantation was performed in 5.2% of ViMAC cases. Thirty–day and 1-year mortality was 34.5% and 62.8%, respectively. Of 40 patients who underwent TMVR, Tiwana et al. reported the outcomes of 28 patients who underwent ViMAC TMVR.3 A total of 57% patients of the ViMAC TMVR cohort underwent attempted laceration of the anterior mitral leaflet to prevent LVOT obstruction, and 11% had preemptive ASA.3 Technical success was reported in 57% of these patients. The 30–day mortality rate was 21%. In addition, 14% of them developed LVOT obstruction. Four patients in ViMAC had either intra-procedural valve embolization or late migration. In a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing patients with or without MAC undergoing either MV surgery or TMVR, patients with MAC undergoing TMVR had higher early mortality risk (31% versus 7%), lower procedural success (64% versus 91%), greater risk of LVOT obstruction (36% versus 4%) and greater need of surgical conversion (9% versus 2%) compared with patients undergoing TMVR for bioprosthetic valve or ring dysfunction.40

Guerrero et al. collected data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology/Transcatheter Valve Therapy Registry and compared the outcomes of patients undergoing ViMAC TMVR with the valve-in-valve (ViV) and valve-in-ring (ViR) TMVR cohorts.41 In-hospital mortality was highest in the ViMAC cohort (18.0%), followed by ViR (9.0%) and ViV (6.3%). All-cause mortality at 30–day follow-up was higher in the ViMAC cohort (21.8%) compared with patients with ViV (8.1%) and ViR (11.5%). Furthermore, the device and procedural success were the lowest in the ViMAC cohort (58.6% and 48.6%, respectively) compared with the ViV (83.7% and 76.4%, respectively) and ViR (68.2% and 59.5%, respectively) cohorts. The rates of ischemic stroke and MV reintervention were higher in the ViMAC group, and LVOT obstruction was the highest among patients with ViMAC (10%) compared with the patients with ViV and ViR (0.7% and 4.9%, respectively). Guerrero et al. also conducted the Mitral Implantation of TRAnscatheter vaLves trial (MITRAL; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02370511) and reported its 1–year outcomes.42 This prospective study investigated the feasibility of ViMAC with balloon–expandable aortic transcatheter heart valves. It enrolled 31 patients, and technical success was seen in 74.2% of cases. LVOT obstruction with haemodynamic instability was seen in three patients, and no intraprocedural mortality or conversion to open–heart surgery occurred. All-cause mortality at 30 days and 1 year was 16.7% and 34.5%, respectively. All–cause 30–day mortality for those undergoing TMVR via transseptal access was 6.7%. At 1–year follow–up, 83.3% of patients were in NYHA functional class I or II, and all patients had ≤1+ mitral regurgitation. Urena et al. reported their single–centre 7-year experience of TMVR in 34 patients with ViMAC.43 Technical success was seen in 76% of patients, and a second prosthesis due to significant paravalvular leak (PVL) related to the malposition of the index prosthetic valve was needed in 26% of the cases. Two cases of haemodynamically significant LVOT obstruction were attested, with one treated medically and the other with bailout ASA. Patients with either preventive ASA or anterior mitral leaflet resection had no significant LVOT obstruction. There was no procedural mortality, but 30–day and 1–year all-cause mortality were 14.7% and 32.4%, respectively.

Table 1: Summary of the outcomes of patients with mitral annular calcification undergoing transcatheter mitral valve replacement

The recently published 2–year follow–up data from the MITRAL trial are the longest follow–up we have to date.44 At 2 years, mortality occurred in 39.3% of patients with ViMAC. Between 1– and 2–year follow-up, one death occurred that was non–cardiovascular, and no hospitalizations for heart failure occurred. Longer–term data on TMVR in patients with MAC are not available yet. Thus far, patients who survive the first year have done well for up to 2 years. The key factors for sustained improvement at 2 years appear to be patient selection from overall clinical condition, frailty, and anatomic standpoint. The published outcomes of TMVR in patients with MAC are summarized in Table 1.

Complications of transcatheter mitral valve replacement in mitral annular calcification

Paravalvular Leak

Assessment of PVL is important as it may be associated with haemolysis or significant haemodynamic issues. The presence of PVL may warrant post–dilation after valve deployment. Residual significant PVL may require transcatheter PVL closure.45 The incidence of haemolysis after ViMAC TMVR has been reported to be as high as 17% at 1–year follow–up.45

Thrombus Formation

The association between TMVR devices and thrombus formation is multifactorial. The vigorous exposure of red cells to large variants in shear stress, high turbulence rate, low cardiac output and resultant slow movement of leaflets can all lead to platelet activation and thrombus formation.46,47 Our practice is oral anticoagulation for at least 6 months, preferably longer after ViMAC TMVR.

Serial echocardiographic and clinical follow–up is required for the timely detection and management of valve thrombosis. New onset heart failure or thromboembolic phenomena should warrant immediate evaluation. Echocardiographic clues such as limited leaflet mobility, thickened cusps, 50% increase in mean gradient or direct witness of thrombus, which is rare, require a detailed imaging assessment with TEE and/or MDCT.

Atrioventricular Groove Injury

Atrioventricular injury and rupture are rare and scary complications that can potentially occur after TMVR. Small left ventricle, MAC and oversized TMVR devices are risk factors for atrioventricular injury.48

Device Migration and Embolization

A malpositioned device or the suboptimal delivery of the device can lead to acute or delayed device migration and embolization.48 Insecure device fixation to the mitral annulus can also lead to this complication, particularly in the case of significant or asymmetric MAC.48 The MV is a dynamic and complex structure, and the dynamic interaction among the components of the entire mitral apparatus can impact device durability and functionality, even if the device was optimally implanted.48 Hence, serial echocardiography and CT imaging studies are required to assess the long–term efficacy of TMVR in general.48

Obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract

As described earlier, LVOT obstruction is caused by TMVR via the permanent displacement of the anterior mitral leaflet towards the interventricular septum, creating a narrow and elongated neo-LVOT. This is a fixed obstruction. The obstruction is dynamic when neo-LVOT generates Bernoulli forces, which attract the anterior mitral leaflet towards the interventricular septum during systole.49 This complication can also occur with ViV, ViR and ViMAC TMVR, and patients undergoing these procedures can develop life–threatening haemodynamic compromise.38 LVOT obstruction is the most common cause of mortality, and small predicted neo–LVOT is the most common reason for exclusion from TMVR.49 Many strategies have been developed to reduce the risk of this complication, such as ASA and the intentional laceration of anterior MV leaflet to prevent LVOT obstruction (LAMPOON).

Alcohol septal ablation

ASA has recently been used as a bailout strategy, as there has been a shift towards using a preemptive strategy. Guerrero et al. conducted a multicentre retrospective review of the outcomes of ASA for treating LVOT obstruction as a bailout strategy.50 It showed that only 4 out of a total of 6 patients survived and were stable at the 30–day follow–up. Wang et al. studied ASA as a preemptive strategy and showed that in-hospital and 30–day mortality post-ASA was 6.7%.51 After ASA, TMVR was successfully carried out in 100% of cases, and 16.7% of patients needed pacemaker implantation after ASA. The median increase in neo-LVOT surface area after ASA was 111.2 mm2. The main limitations of this procedure include unfavorable septal perforator anatomy and inadequate interventricular septal thickness.

Laceration of Anterior Mitral Valve Leaflet to Prevent left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (the LAMPOON procedure)

The laceration of the anterior MV leaflet is a catheter-based electrosurgical procedure in which the anterior MV leaflet is lacerated before TMVR. By lacerating the A2 scallop, the anterior mitral leaflet splays when displaced by the TMVR device, exposing the open transcatheter heart valve cells, which would have been otherwise covered by the anterior mitral leaflet. The details of this technique have been described.52,53 In the prospective NHLBI DIR LAMPOON trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03015194), 30 patients at prohibitive risk of LVOT obstruction were assisted by the LAMPOON technique.49 The survival to the immediate procedure was 100%, and 30–day survival was 93%. There was no incidence of stroke, and primary success – defined as successful TMVR without reintervention and LVOT gradient <30 mmHg (optimal) or <50 mmHg (acceptable) – occurred in 73% of cases.

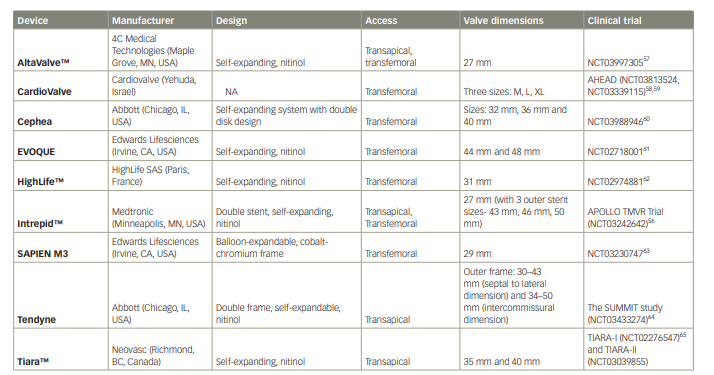

Dedicated devices for transcatheter mitral valve replacement

Dedicated TMVR devices are being evaluated in patients with MAC, and early data in the MAC cohort have been reported. Three studies including a total of 36 patients evaluated the use of the Tendyne™ valve (Abbott Structural, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in patients with MAC and achieved favourable outcomes with low mortality rates.46,47,54 Further promising large–scale studies of the Tendyne and Intrepid™ (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) valves, which will provide additional information on the role of TMVR in MAC, are under way.55,56 The characteristics of other TMVR devices currently under study are summarized in Table 2.57–66

Table 2: Characteristics of various transcatheter mitral valve replacement devices

NA = not available; TMVR = transcatheter mitral valve replacement.

Conclusions

TMVR is a promising strategy, even though the progress in this field has been slow. Careful and thorough imaging is essential to identify the risk of LVOT obstruction and other procedural complications. Outcome data for TMVR in MAC thus far have demonstrated a high rate of complications and significant short- and mid-term mortality. Further large-scale studies and clinical trials are needed to assess the safety and efficacy of TMVR in MAC patients.